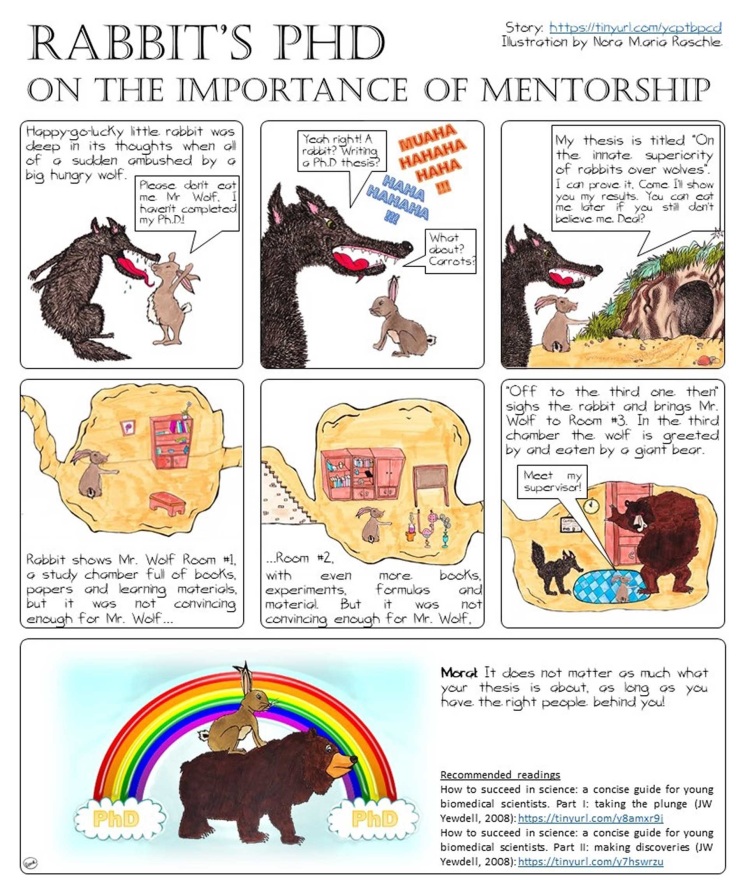

We are shaped by the experiences we make and the people we meet. Mentorships are some of the most, when not the most, important relationships we build during our scientific careers. Different people of various ages and backgrounds may become your mentors. The key is to see a learning opportunity in front of you – no matter how old you are or what stage of your career you are in. There are two consecutive publications that have targeted the topic of “How to succeed in science“. The importance of mentorship is depicted within a short anecdotal tale therein. It is about a young rabbit on its way to writing a PhD thesis and illustrated below.

On this page you can find short interviews with researchers from all over the world and with various levels of expertise. Expe(e)rtise, since this is knowledge from your fellow peers. May these inspire, guide you or make you feel less lonely on your own bumpy road down all of the present or expected scientific highs and lows.

Original articles on how to succeed in science:

07/19/2018: Throughout the past year we have been privileged to interview a wide variety of academic experts in this special mentoring section of our blog. No matter what challenges were brought up, the fascination for science was undeniably present in all the stories. This is also true for this week’s interview with Jason Shepherd, Assistant Professor of Neurobiology and Anatomy at the University of Utah, outdoor-lover, photographer, science communicator and world traveler. Jason’s passion for science emerged early, but despite acknowledging the challenges in academia, his fascination for science remains unshaken. In his interview he shares valuable early career insights, but also highlights that next to achieving your goals, mental health is an important and non-negotiable point to remember.

Jason Shepherd (38y), Assistant Professor of Neurobiology and Anatomy, University of Utah, USA

How did you get into research?

Research was a natural road for me, as I have always been curious about how the world works. I initially started the MD route in New Zealand, where entry was at the undergrad level but ended up doing one elective in neuropsychology and got hooked on the brain.

Do you still remember the first time you were fascinated by science?

I was incessantly asking my parents questions about the world. I remember once asking my mom (an English teacher) why the sky was blue and she made up a story about fairies to humor me. Apparently, even at 5 years old, I wasn’t convinced and told her this explanation was nonsense. Luckily, I had parents who allowed me to explore on my own and supported my forays into the library. I never felt constrained or told that my curiosity was a bad thing. I find it sad that as adults, we often lose that sense of curiosity for the world.

Shortly described, what is your focus?

We are focused on understanding how information is encoded, stored and retrieved in the brain at the cellular and molecular level. We are also interested in how these processes go awry in neurological disorders.

What is it that fascinates you about research and science?

Science is a process, a successful one, that attempts to explain and understand the world we live in. To me, there’s nothing more exciting than being the first to discover new knowledge that adds to our understanding of reality.

What are the biggest challenges?

There are many: at the systemic level, obviously funding is the biggest challenge. In the US, the funding rate for my area of research is around 10-15%. This makes obtaining grants very competitive. There’s also challenges in publication and getting your work out. Peer review is still the gold standard, but there’s inherent bias and issues with how it is carried out. The good news is that there’s a movement to change and improve the system; from open access journals to preprints where the work is put online prior to submission.

If you could improve something about the academic system – what would it be?

In an ideal world, scientists get the freedom and resources to follow their curiosity. When funds are low, metrics and tangible “products” become the method of distinguishing who’s “better” or more productive. This stifles innovation in my opinion. Other than increasing funding, the solution to this isn’t obvious. I do like the idea of moving towards funding the person, rather than a particular project. Much of science, despite it being hypothesis driven, is exploratory and it’s hard to predict where the new break-throughs may come.

If you were to start over with your academic career tomorrow, would you choose it again? What would you do differently?

Yes, despite the challenges and sacrifices. I can’t think of anything else I would rather be doing. My career has taken me to places that are far from my family and this can be tough. I’m not sure if I would redo anything, hindsight is 20/20, but I’m looking forward to the future rather than looking back.

What does it mean to be a scientist? Which abilities are most important to bring along?

A scientist is someone who does science, which seems obvious, but this can take many forms. In its purist form, you are doing the experiments yourself but science can also involve pure theory. In running a lab, I rarely do the science anymore. This is a big quirk of academia, we are trained as experimentalists but running a research lab requires skills more suited to a small startup; managing people, balancing budgets, and writing grants.

In terms of abilities, you have to be motivated in science. It’s an inherently self-motivated profession. This also requires persistence and “grit”, in that you have to grow a thick skin. Science is 90% failure! Experiments may not work, results may not be as expected and then there’s the rejection you have to face in funding/peer review. Beyond these intangibles, good skills to have include: organization, writing, communication in general and logical thinking.

What is the most important thing you would tell…

…a student interested in doing a PhD?

Get as much research experience as you can before applying to do a PhD. Make sure this is the right road for you. Then make sure you find the right place, where you can maximize the chance of studying a problem you’re going to want to solve.

…a post-doc?

Perhaps even more important than your PhD lab, finding the right postdoc lab is key. Make sure the PI is supportive of their trainees both during and after they leave the lab. Find a lab that fits your research goals, but also where you can thrive as a scientist. The group dynamics are critical, ask blunt questions of the current postdocs/students and see if they are happy with the lab environment.

…an early career scientist?

Persist! You’re going to face an incredible number of hurdles to get everything up running. Things are much slower than you’re used to, but don’t get disheartened. Be picky with your first hires/students…they set the tone for the lab. Find supportive faculty and mentors at your university. Don’t feel like you have to do everything on your own…ask for help.

As a scientist, is there room for hobbies?

Of course! In fact, I highly recommend having outlets outside of science. Having hobbies can help with your mental health, and even help with focusing your science as you can avoid getting burnt out. For example, I love the outdoors and recently got into landscape photography. It helps that Utah is full of amazing parks and beautiful landscapes!

Are there responsibilities of being a scientist that you think should receive more value?

Yes, mentorship. Frankly, good mentorship is often not rewarded and this needs to change. The “human” element of science is real and mental health issues are common. Some of this can be offset by good mentorship. I would love to see good mentors rewarded and a system that disincentives bad mentorship.

How do you plan for your science to impact society?

Not all science directly impacts society, but it often does. Scientists should think about how their research could potentially impact the world, whether for good or bad. Part of this is directly communicating with the public, which scientists often don’t do.

How can science be taught to children and is there a point of doing so?

Everyone benefits from an educated and well-informed public. This starts early. I think the biggest issue with science education is that it’s mostly taught in a way that emphasizes facts but doesn’t allow children to understand HOW we got those facts. The process of how science is done should be taught first. Give children those critical thinking skills early, and they will run with it.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

I think this goes without saying but enjoy the journey. It can be tough and the world can seem like it’s beating up on you. In the end, if you love science, it is an incredibly rewarding profession.

To read more about Jason Shepherd’s research, see also:

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jason_Shepherd

https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=11LOZy0AAAAJ&hl=en

https://www.linkedin.com/in/jasonshepherd1/

https://twitter.com/JasonSynaptic

https://www.facebook.com/shepherdlab/

And some more of his amazing photography can be found at: https://www.instagram.com/blindsight_photography/

And some more of his amazing photography can be found at: https://www.instagram.com/blindsight_photography/

05/04/2018: This week’s interview is answered by Tomás Ryan, an Assistant Professor of Neuroscience at Trinity College Dublin (TCD), Ireland. From knowing Tomás personally, I can say that he is not only one of the most promising scientists in memory research, but also a genuine supporter of efforts in science communication, equality and early career support. I am therefore particularly happy to sharing this interview with you this week.

Tomás Ryan (middle, 33y) and his team. Tomás is an Assistant Professor of Neuroscience at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland

How did you get here?

I completed my undergraduate degree in Genetics at Trinity College Dublin. The year I began at university was the year that the human genome was published, and I quickly realized that all of my burning questions about genetics and what constitutes biological life could be answered simply by reading textbooks and journal articles. During my third undergraduate degree I attended a guest lecture by a Drosophila (fruit fly) geneticist who’s research focus was the formation of long-term memory. I walked in to that lecture as a geneticist, and I walked out a hopeful neuroscientist. After following the speaker to the pub I attempted to persuade him to take me as a summer research student. Instead, he sent me to his close collaborator’s group at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Mumbai, India. There I spent months developing behavioural assays to study olfactory conditioning in fruit fly maggots and immersed myself in the neurobiology of memory. After this experience I decided to do my PhD in the molecular biology of behaviour, but at some point in my fourth undergraduate year I became a vertebrate snob. I arrived at the very unoriginal, and flatly wrong position of assuming that to understand memory one needed to focus on a more complex mammalian organism – the mouse. Partly because of this bias, and partly because of good fortune, I moved to the University of Cambridge and Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute to undertake my PhD in molecular neuroscience. My PhD experience was typical in all the good and bad ways, but I had a supervisor who was uniquely liberal and encouraging in project direction and allowed me to integrate my background in evolutionary genetics with molecular neurobiology. While this approach was productive, I became very disillusioned with the radically reductionist epistemics of molecular neuroscience. We would engineer the mouse genome in very, very specific ways, and identify highly specialized behavioural and physiological phenotypes. But then we would literally mash-up whole brains and do gross biochemical experiments from which we derived cartoon-like models of what we thought might be going on in the brain. I knew this approach would never really answer the questions I had about memory. Fortuitously, I found myself spending increasing amounts of time in the Experimental Psychology department at Cambridge. Through attending seminars and conducting experiments there I found my own scientific taste, and I learned how to integrate serious theory with hypothesis-driven experimental design. But I also saw that the techniques of behavioural neuroscience were stuck in the 1970’s and most practitioners had an overly conservative scepticism of any new methodology. I knew this attitude was not only wrong, but unsustainable, owing to the development of optogenetics by Karl Deisseroth and others at Stanford. So I sought a Postdoctoral lab that was addressing big questions in the memory field and was not afraid of using the latest experimental techniques regardless of risk. I found myself in the group of Susumu Tonegawa atMassachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) working on new methodology for labelling and manipulating specific memory representations (engrams) in the mouse brain. With an uniquely outstanding group of colleagues I spent six exciting years attempting to moderately push the boundaries of what we know about memory engrams In 2017, and after over a decade abroad, I returned to Dublin to set-up my own research group because I think that Ireland (and Europe) is an excellent environment to grow a new lab, and I see many opportunities for developing the research environment here. My research group’s over-arching aim is to understand how memory, and instinct, can be stored in the brain.

Shortly described: what is the focus of your research?

Understanding how information can be sustainably and plausibly stored in the animal brain, and how this process is modulated by learning, development, and evolution

What is it that fascinates you about research and science?

I am most fascinated by the mind, and how it comes into being through our experiences, our development, and our biology. I want to understand how we got here, and use that knowledge to help inform how we may develop in the future.

Can you name the biggest challenges?

The brain is the most complex structure in existence. Mind and behavior are two related and extremely perplexing phenomena that we still do not have adequate theoretical frameworks with which to explain. Yet research into neuroscience requires the integration of all three aspects of animal life, as well as the mastery of innumerable and constantly developing experimental techniques. Doing this is obviously full of immense challenges, but we have clearly made some progress in the past 100 years so there is every reason to be optimistic about the next. I am however very concerned that the biggest challenge facing the future of science is a degenerative political climate in combination with dwindling resources and over-population. For this reason I think academics have a responsibility to engage much more with the public in order to promote a more democratic and fact-based society even if our academic career structures do not incentivize this seemingly tangential but necessary activity.

Looking back at your experiences, what’s your most important recommendation for…

…a student deciding upon her/his field

Choose whatever field and sub-field you are most interested in and follow the questions that you yourself are interested in. If having studied a field, you realize that all the questions you are interested in have already been answered, change your field. Keep changing until you arrive at your research focus – what do you really want to know that you can’t learn from a library? What in science do you think about while walking through a park or museum on a Sunday afternoon? Science is a continuing journey of investigation and discovery, not the learning of an established body of facts.Always stick to questions. Answers are usually boring, but they lead you to refine the original question and open new doors. All science is refining bad ideas. We are all stumbling around in the dark, trying to be a little bit less wrong with each step.

…a doctoral candidate choosing a topic an research group

Your PhD lab should have three essential features. First it should be in the broad scientific area that interests you most at that point in your development. Second, it should be a competent and productive lab that will enable you to learn techniques and deliver significant and recognizable research outputs. Third, it should be a place where you can see yourself functioning, every day, in a happy and motivated state. Carefully investigate any research group you consider doing your PhD in. Avoid research groups where you can sense uncomfortable levels of anxiety, stress, or depressed attitudes. Above all, be open to learning as many new ideas, techniques, and perspectives as possible. By the end of your PhD you should have a clear idea of your long-term research direction, and it probably won’t be the topic of your PhD. Maintain an active personal and social life outside of your PhD – it make life and science better.

…a postdoctoral researcher

Chose a new research topic that both complements your PhD research and directly leads into your independent research career. Take charge and be bold – your postdoctoral career may be your best and/or last opportunity to do truly high risk science. At the same time be cautious, and avoid joining seemingly impressive research groups where very few people are successful. Develop a good relationship with your Postdoctoral mentor and always work collaboratively with them. Always look after your mental health.

…an early faculty researcher

Find the right environment for you to work in and develop your research programme. Do not necessarily go for the most prestigious or fancy institutions. You are one data point and you will not represent the average performance level of whatever university you end up at. Choose an institution that is the best individual fit for you and your group. Then the most important thing is to invest a LOT of time and effort into recruiting the best people to your group. For European institutions, getting significant funding in advance of accepting an offer of a position is a huge advantage. Negotiate hard for everything – whatever you ask for that you need is an order of magnitude more valuable to you than it is to the university.

What’s your approximate success/rejection rate for (papers/grants/job applications)?

I’ve never estimated it, but I have been fortunate.

We are all great in handling success, but what’s your mantra to handle rejections?

Rejection is just a part of the academic process. If you know you have something genuinely new or valuable to say, and you persist, then you will eventually succeed. Frequent rejections are an unavoidable reality of the over-crowded and hyper-competitive academic environment. If the system is working, then rejections are also precious opportunities to receive frank and invaluable feedback that we normally don’t receive from our closest friends and colleagues. However, I also worry that paper and grant rejections can often occur simply due to reviewer laziness or political agendas. Regardless of the cause or rejection, wrestling with the academic environment should be much less challenging that dealing with failed experiments and the difficulties of actual scientific investigation. I have been very lucky that this has so far been the case for my own situation. I don’t know what my attitude would be if that balance of effort shifted to the academic side.

Success is not always easy to handle either. One piece of advice from my Postdoctoral mentor still resonates with me: “Katte kabuto no o wo shimeyo”, translated as “After victory, tighten your helmet strap”.

Where do you think the future of your field lies? What are key challenges we have to overcome?

I don’t know where the future of my field lies, but I am sure that it will be formed by individuals who focus on making progress through curiosity-driven science rather than the machinations of big data and research policies aimed purely or primarily at methodological development or translational research. We know so little about the brain that we should not be constrained by any scientific dogma or particular philosophical approach. As long as we support young researchers to do what they’re interested in, we’ll make progress.

Is there anything else you always wanted to tell a fellow scientist (younger or older) or any person interested in science?

I tend to tell younger scientists that science is not a career. It is not something that one should chose as a potential alternative to medicine or law or business or whatever. Science is an activity. It is an investigative and creative process that transcends the trappings of the academic career structure (position, salary, awards, and responsibilities). For the science to be done, and to survive as scientists, it is necessary that we engage in the processes and structures of academia. But it is important to keep in mind that all of the realities of academia – universities, funding organizations, journals, awards, etc – are just tools with which to get the actual science done. Focus on the question, and get to an answer.

Telling things to older scientists is usually a waste of time. Usually.

Cat or a dog person?

Innately a dog person, but experience has turned me into a cat person because dogs need to be walked.

You can also find out more about Tomás Ryan at:

Twitter: @TJRyan_77

https://www.tedmed.com/talks/show?id=624548

04/03/2018: Gábor Csifcsák is a neuroscientist and father of two, currently working as postdoctoral research fellow at the Department of Psychology of The Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø. In his interview he describes his personal journey, talks about his fascination with the ever-changing nature of research and describes uncertainties that scientists have to face. Gábor also shares valuable tips for students interested in science and presents some suggestions for the improvement of the field.

Gábor Csifcsák (40 years), postdoctoral research fellow at the Department of Psychology,

The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway

How did you get here?

I obtained a diploma as a medical doctor at the University of Szeged (UoSz), Hungary, and started working on my PhD at the Department of Psychiatry of the same university. My work focused on neural activity related to the processing of simple auditory stimuli in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Later, I also worked on the effects of a non-invasive brain stimulation technique called transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on pain perception in healthy adults. Given that I was always more interested in research than medical work, in 2007 I started working at the Department of Psychology (UoSz), where besides teaching anatomy, physiology and cognitive neuroscience to psychology students, I also supervised work at the Electroencephalography (EEG) Lab. Here, we focused on recording and analyzing brain signals (event-related potentials and oscillations) related to the processing of visual stimuli in health adults and school-aged children. In 2016 I applied for the postdoc position in Tromsø, because I wanted to change my focus of research and work again with non-invasive brain stimulation techniques and investigate their effects in neuropsychiatric conditions such as depression and chronic pain.

What is your focus?

Currently, we are working on establishing a new tDCS paradigm that would be more efficient in improving certain cognitive symptoms in depression and chronic pain. In particular, we use a special card game task that enables evaluating how people learn from reward and punishment to optimize their decision-making. We use tDCS to improve their choices, because we believe that this might lead to beneficial clinical outcomes in these disorders.

What is it that fascinates you about research and science?

It is ever-changing and you always learn new things! I am fascinated about what we’ve already learned about the functioning of the brain, but even more about those things we still know very little about. It is fascinating to think about how activity in our nervous system might be related to human behavior and subjective phenomena such as feelings, thoughts or dreams. Conducting research is sometimes frustrating, but it can be extremely exciting to test your own hypotheses.

What are the biggest challenges?

Facing uncertainty, I guess. You can never be sure about what the outcome of our research will be, you can sometimes realize too late if something went wrong with the research, and of course, you can never be certain about how other researchers, journal editors and reviewers will respond to your findings. Also, it is very difficult for me to lean back and have a rest without thinking about something related to my work, because it never really ends. Sure, by publishing a paper you can finish a project, but there are always more projects running in parallel, and of course, you always have to think ahead by finding ways to finance your research.

Looking back at your experiences, what’s your most important recommendation for a student deciding upon her/his field?

For students interested in science and research, I would recommend focusing on learning methods for data collection and analysis very well. Statistics and programming are of key importance even if it takes much effort from your side. Also, when searching for a PhD position, I think that finding a helpful and experienced supervisor is more important than conducting research in the topic you are most interested about. You’ll have time doing your research later, when you’ve acquired the basic skills.

Do you feel that you had to sacrifice a lot to get to the position you are in today?

Not really, I’m happy to work in this field and I can’t really think of doing anything else. Actually, sometimes I regret not sacrificing more in my junior years.

What are the challenges you are facing in your everyday life? Can you give some advice for the upcoming generation of researchers?

Finding time for everything can be hard. As I mentioned earlier, it can be really difficult to relax when I’m really immersed in a project. I think that you should have a hobby that you really enjoy (e.g., sports, playing an instrument, etc.) in order to get away from science for a while.

If you could change 3 things about the way the academic system works right now what would they be?

- Science should be more transparent: researchers should make their data and alaysis methods available to everyone and all publications should be open-access.

- On the other hand, reviewers and even action editors should be blind to the names and affiliations of manuscript authors.

- Conference talks should be available online.

Being a scientist with kids do you feel that it is hard to balance family and work life? Do you have any suggestions or encouragements for readers?

Yes, it can be difficult. During the years, I learned to lower my expectations about my scientific career and I think this was for the benefit of my family life.

Is there anything else you always wanted to tell a fellow scientist (younger or older) or any person interested in science?

Science is for everyone and it is never too late to be a researcher!

What did you want to be as a kid?

A detective.

Cat or a dog person?

Fish.

01/14/2018: Ines Mürner-Lavanchy is a Swiss postdoctoral research fellow currently working at the Monash Institute of Cognitive and Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Melbourne, Australia. Ines works as a developmental neuroscientist and is conducting neuroimaging research studies with children born very prematurely. In her interview she talks about her fascination with research and science, how it is to conduct neuroimaging sessions with young children and what it means to study and work far away from her home country.

Ines Mürner-Lavanchy (30 years), postdoctoral research fellow at Monash Institute of Cognitive and Clinical Neurosciences, Monash University Melbourne, Australia

How did you get into research?

My Bachelor studies were already way better than what I had expected (I started not really knowing what to expect from studying psychology). However, it was the deeper understanding of cognitive, experimental and neuropsychology I got during my masters, which sparked my interest in science. I always loved asking questions, learning, discussing and deepening my knowledge in certain areas.

When I first met my Master’s thesis supervisor, she told me that clinical research with children was not like what we had learnt at University. I think what she meant was that strict rules about experimental setup can for example be relatively hard to comply with in children, particularly when working with those with cognitive difficulties. While that really puzzled me at first, I wanted to accept this challenge.

What is your focus?

My work focuses on understanding cognitive and brain development following early brain insult. More specifically I work with children born very prematurely. I am further interested in environmental and personal factors that can influence child development and possible benefits of interventions to improve long-term neurodevelopment. I use a combination of measures, including neuropsychological assessments, behavioural questionnaires and neuroimaging.

Neuroimaging studies are quite common in adults. What about neuroimaging research in children or infants?

Neuroimaging with young children can be quite challenging. It is important to prepare children well before scanning, so that they will not be scared by the scanner surroundings. We try to introduce children carefully by showing them everything in detail and simulating the loud noises beforehand. When conducting a task within the scanner, we make sure to train the task previously. Just like in photography where movement can lead to blurry pictures, movement in the scanner blurs brain images. The more relaxed the child is, the better is her ability to lie still in the scanner. Therefore, we focus a lot on assuring the well-being of our participants. Personally, I have not conducted neuroimaging sessions in children under the age of 7 yet. But, there are a few groups which demonstrate how to conduct neuroimaging even in babies: Once the babies are fed, swaddled and put to sleep. It is actually feasible!

What is it that fascinates you about research and science?

How can anyone not be fascinated by science? For me, research is about asking questions, answering them and questioning the answers again. This can be exciting in any area I could think of, but even more so in brain development in children. I always loved getting to the bottom of things, and I am naturally very curious. I am just so amazed by the world we live in, the nature, the human body and mind and I love learning about the ‘mysterious workings of the world’. I am equally aware of the possibilities for change if we know which mechanisms make change possible and use our creativity to apply them.

What are the biggest challenges?

As researchers, we are very privileged to be able to work in a field of our interest. We should be very careful and responsible with our resources (keyword: tax payers’ money), be really productive and conduct relevant research. At the same time our research should be scientifically rigorous, and we should not bow to the pressure of publishing heaps of “sexy”, selling results, which have no substance. I also think that it is important that we communicate our results to the lay public and contribute to dialogue on relevant social, political or economic issues across disciplines. I consider it as a big challenge to follow all these ideals.

You are currently working abroad. How did a Swiss researcher end up in Australia?

The lab I work with at the moment is one of the most successful labs in my field and I always admired my now supervisor from far. I have been very lucky to getting the chance to working with Peter Anderson and his team. I have learnt so much and have had a very productive time. Studying and working abroad can help to build connections with leaders of one’s field, and broadens one’s horizons. You get to know a lot of people, a different work environment, a new work culture. It is a great experience and benefits not only professional but also personal development.

How often would you consider your job to be rewarding and how often do you also have to deal with rejection or feedback that makes you question your work?

I think in comparison to other jobs, you receive quite a lot of external feedback in research, which can be very nice, but also very frustrating. That can result in huge fluctuations of motivation. To stay balanced, I try to focus on my internal motives. For that reason, I experience my job to be rewarding almost every day: how exciting is it to be able to work in a field that you absolutely love? I also really enjoy reading, writing, supervising students, running analyses, improving my coding skills, discussing results with colleagues and working with children and their parents.

What did you want to be as a kid?

A world explorer!

For more on Ines Mürner-Lavanchy’s work and the work of her research group check out the following homepage/link. You can also find Ines on twitter: @MurnerLavanchy

Furthermore, we are excited to letting you know that @MurnerLavanchy and @bornascientist are currently collaborating on developing an information section on the relationship between preterm birth and brain development. Stay tuned for more!

12/18/2017: Sophie von Stumm is Associate Professor for Developmental Psychology at the London School of Economics & Political Science (LSE). In her interview, she talks about her own, not always straight-forward way into science. She highlights how trying to fit into the expected structures of science bears the risk of compromising ones’ own interests. Sophie also shares challenges she faces in her career until today, and finds honest and encouraging words on how to deal with rejection.

Sophie von Stumm (33y), Associate Professor for Developmental Psychology at the London School of Economics & Political Science (LSE)

How did you get into research?

When I studied for my undergraduate degree in psychology at Royal Holloway University of London, I expected to build a career in Human Resources (HR) afterwards. To explore this possibility, I interned after the second year of my undergraduate studies for 3 months in the HR Department of a big, international company in Berlin. Within the first week I realised that I was neither cut out for HR nor for big, international companies. I spent my days staring at big clock on the wall in front of my desk, begging the clock hand to move faster so I could go for lunch or home. I completed the internship and returned to London to finish my degree and during that process I fell in love with doing my dissertation project. After that I knew I wanted to do more research projects, and so I registered for a Master of Science degree and then applied for PhD studentships.

What are the biggest challenges?

I think that one of biggest challenges that early career researchers face is avoiding to become lost in the professional structures of science. We live and work in times when hiring decisions and promotions depend heavily on metrics, for example the impact factor of the journal you publish in or how often your work has been cited by others (the so-called h-index). Also, early career researchers tend to be evaluated by the amount of grant money that they’ve secured: Getting grants is surely impressive but no guarantee for doing good research. The current structure of science can trick you into designing research that is more likely to be funded, rather than the one that you’re actually interested in. Trying to fit hiring and promotion criteria can distract from pursuing the research that we are passionate about.

How often would you consider your job to be rewarding and how often do you also have to deal with rejection or feedback that makes you question your work?

I receive rejections or feedback that critiques my work almost every day. If you get into science, you will soon learn that a substantial part of your job is asking others for things (for example publication, money, research support) — others who have the power to say ‘no’. At the best of times, they will tell you then why their answer was no. And that is when you learn and improve your work.

My first journal publication was my MSc dissertation. The re-write from the dissertation to publication format was traumatic. I was working with a fantastic team of senior scientists, who changed every single word and structure in my dissertation, before they agreed that the manuscript was ready for submission. I was devastated: All my brilliant phrases and witty paragraphs had been transformed into serious science writing. But I didn’t know that the real trauma was yet to come. The reviewers pointed out that my statistical analyses were completely flawed and inadequate, on top of asking for further re-writes of the text. For the next month, I holed up in defiant wrath, promising to never touch this manuscript or journal again. Then I swallowed my pride, sat down and started the analyses from scratch. Over the next few weeks I learned a lot about factor analysis, structural equation modelling, and the treatment of missing data. It took two more rounds of reviews until the paper was accepted. But when it was, I knew that its conclusions were based on accurate statistics (and that my stats skills were superb). I will not pretend that I thought the reviews were ‘nice’ but ultimately, they were constructive — they made the paper stronger and me a better scientist. I try to view all rejections and critiques from that perspective, although it’s of course a different question how successful I am with it.

Manuscript rejections are hard and maybe even crushing – especially around the holidays. However, there is always a little bit of truth and a chance to improve behind every critique (Illustration by Nora Maria Raschle @bornascientist.com).

Most of us enjoy the upsides of science, but how do you deal with rejections?

I have three key recommendations for how to deal with rejections.

First, take them slow: When I receive a notice of rejection for a paper, I often let it sit in my inbox for a few days until I know I am in the right frame of mind to read through the critique. I print reviewers’ comments and I work through them one by one, scribbling notes and responses to each. These notes are only for my eyes: They are the private space to express disagreement in various forms, including rude and angry if necessary. Then I drop the printout in a drawer for a week or two until I know I am ready to re-read the comments, understand them, and change the manuscript accordingly. It might strike you as a very slow process to deal with paper rejections but keep in mind that scientists tend to be emotionally attached to and proud of their research. At least for me, it takes time to transform the disappointment over a rejection into constructive revisions.

Second, be stubborn: redesign, rewrite, reanalyse and resubmit. Think carefully about what you need to do to improve your work so it becomes worth publishing. Then go and do it.

Third, celebrate when you submit: In a business where rejections are daily occurrences, make the moment count when you completed a piece of work that you are proud of. Don’t wait for the acceptance letter to crack open the champagne: It often comes after several rounds of revisions, by the time of which you will have moved on to a different research project and your excitement about your earlier work has lessened.

What did you want to be as a child?

A novelist. Failing that an actress.

Sophie von Stumm is also online: on twitter @hungrymindlab) and at her homepage www.hungrymindlab.com.

11/27/2017: Audrey Peyper is a PhD candidate in history, mother of two and writer on the subject of metal. This week, we are very excited to have not one, but three (!) experts involved in our interview. In the first part of our interview, Audrey talks about the challenges and excitements of academic life, but also shares her perspective as a scientist and mother of two young children. In the second part, her daughters Roxy and Angelique (4 and 7 years) talk about what they think their mom is doing, what they want to be once they grow up and what the best thing about their mom is.

Audrey Peyper (33y), (nearly finished) PhD Candidate in History,

University of Tasmania, Australia

How did you get into academia?

I wanted to create a job for myself that was interesting, so I kept studying!

What is your focus?

Historical economic theory, religious ideas concerning power and colonial sites influenced not by formal or ‘settler’ colonialism but rather economic imperialism and evangelism.

What is it that fascinates you about your topic?

Being able to interrogate questions of freedom, human rights, and formative processes of the modern world.

What are the biggest challenges?

The challenges are also the exciting part. The sites I work with in the colonial Pacific Islands misalign with many established models which is difficult to examine but prompts important questions. Access to archives is a practical challenge that requires a lot of travel and sometimes careful negotiation, alongside many hours of difficult reading (with some exciting discoveries!)

Looking back at your experiences, what’s your most important recommendation for….

…a student deciding upon her/his field?

I would make two points. Firstly, to study a variety of subjects before settling in on a single field is a great way to bring a unique set of skills to your field, and will help differentiate you from others. Secondly, try to pursue the field that genuinely interests you, rather than thinking too much on potential work or money and so forth. The PhD is a long, difficult degree and it will be passion and interest that keep you going. Furthermore, you will be more successful in a field that you are passionate about and more likely to create a niche for yourself.

Do you feel that you had to sacrifice a lot to get to the position you are in today?

I have been at the University for 14 years now, all through my 20s and now into my 30s. This has meant a delay in other life things such as buying a house, being able to travel for leisure, accruing superannuation for retirement, and stability of housing and finances for an extended period of time. It can be exhausting! These things mean more once you have children, and it can really feel like you are ‘behind the pack’ for your age group in terms of becoming established in life.

What are the challenges you are facing in your everyday life (i.e. in keeping a healthy work-life balance)? Can you give some advice on what worked best for you?

Definitely it is hard to balance the demands of young children, maintaining the house, and earning money alongside sustained research, especially if the research is unfunded or you are ‘between jobs’ (which is a lot of modern academic reality – moving from contract to contract). Getting enough work done to be a competitive academic when you have many things also making demands on your time and energy is a real challenge. Resolving this is not easy, and I have found that ‘compartmentalising’ time is important – to be very strict with what I am doing in a given block of time (whether research, spending time with children, or working, etc.) and not thinking on the other things in that time, to avoid feeling overwhelmed.

What are your distractions when you are not studying? Is there time for hobbies?

There is not much time (or money!) for hobbies but it is important to make time for things that make you feel happy or are good for your health. Exercise is something I am trying to do more often, though I am not so great at it! My main distraction is my interest in music. I write for a music magazine which is really exciting. I find this is a good task to take my mind off my research but also keeps me writing every day, as momentum is key to sustaining writing.

If you could change 3 things about the way the academic system works right now (publication, funding, hierarchy etc..) what would they be?

- The heavy focus placed on amount of publications for postdoctoral fellowships, often rather than quality.

- The availability of teaching work for PhD students is diminishing yet many jobs require fairly extensive teaching experience including designing courses that simply isn’t available to many finishing candidates.

- Short term (1-3 year) contracts for fellowships or lectureships. It means that early career researchers have to move around the world frequently to secure work – while I don’t mind this in itself and it does make academia prohibitive to many, it is expensive to facilitate and creates in between periods of no income which is very hard on families.

Is there anything else you always wanted to tell a student?

To embrace a life of scholarship is, in many ways, its own reward. It won’t always be easy but be patient and have faith in yourself.

What did you want to be as a kid?

I wanted to be a famous artist!

Do you know what your mom is doing? How would you describe her work?

Angelique (7y): Her PhD is a really big book that is extremely important I think it is about when the islands battle across territory and stuff, historians look at history and write it down.

Roxy (4y): I have no idea, I think it is about the things she likes.

Do you think that’s a fun job?

Angelique: No – because you just sit there typing and thinking, it sounds boring. But if I were a zoology researcher, I would learn about all the different animals and new ways of doing things.

Roxy: I want to be just like mummy.

What do you want to be one day?

Angelique: I would like to be a famous performer or singer, part of a band or acting troupe, or a zoologist.

What does your mom think about that?

Audrey (mom): My response… fantastic! a life in the performing arts is a lot of fun but also a lot of hard work! Zoology sounds fascinating.

Roxy: A paleontologist, and an artist and a ballerina.

What does your mom think about that?

Audrey: I think they go really well together!

What is the best thing about your mom?

Angelique: Fun, friendly, clever, talented.

Roxy: She hugs me and she loves me

11/20/2017: Psyche Loui is an Assistant Professor of Psychology, a musician and mother. In her interview she gives insights on what fascinated her to start studying music and the brain, how it is important to be fascinated by a scientific question while also focusing on learning the methods required, and highlights those challenges she would like to change within the academic system (i.e. missing transparency, publication biases and research funding).

Psyche Loui (36y), Assistant Professor of Psychology,

Neuroscience and Behavior, and Integrative Sciences at Wesleyan University

How did you get into research?

I have always loved music and played violin and piano from a young age. I also love science, and thought I was going to medical school to become a doctor. But during undergrad years at Duke University I realized from my classes that there is a field of research called Cognitive Neuroscience, where we can study things that might seem mysterious and unscientific, like our thoughts and perceptions and feelings, with the help of good experiment design and some useful tools such as brain imaging and electrical recordings from the brain. I learned that people were starting to use these tools to study how we hear and learn and form preferences for music, and I wanted to get in on it. I’ve been studying the Cognitive Neuroscience of music ever since.

What is your focus?

Music and the brain.

What is it that fascinates you about research and science?

I love asking questions and finding answers to them. There are always important new questions that have not yet been asked, and there is always more to learn. I am also motivated to use what we learn to design something applicable to the general public.

What are the biggest challenges?

Everything always takes 10 times longer than you expect it to.

Looking back at your experiences, what’s your most important recommendation for….

…a student deciding upon her/his field

Follow your passion. If there is some question that keeps you up at night, and if you love the process of pursuing that question, then that’s the field for you.

…a post-doctoral researcher

Start by pursuing the low-hanging fruit while learning some new techniques, then move on to more ambitious questions.

…a junior faculty

Spend the first year getting to know your colleagues and some students really well so that you can learn about the culture of your institution from multiple perspectives. Then you’ll have an easier time working within your system.

Do you feel that you had to sacrifice a lot to get to the position you are in today?

No. I have a longer commute than I’d like, but in general I have been quite lucky.

What are some of the challenges you are facing in your everyday life (i.e. in keeping a healthy work-life balance) and do you have any advice to overcome these?

Students often want to meet at inconvenient times given my parenting schedule (I have a 2.5-year-old daughter and have to do all drop-offs and pickups for her daycare). I think one solution has been to use online tools as much as possible (online schedulers, chat programs e.g. Slack), but I am still figuring it out.

If you could change 3 things about the way the academic system works right now (publication, funding, hierarchy etc..) what would they be?

- Academia often operates in a shroud of secrecy under the guise of protecting the privacy and confidentiality of people involved. The result of this secrecy is that many important decisions in academia can be driven by a small number of individuals, each with their own biases and limited knowledge. I think most people would benefit overall if the system was more transparent.

- I wish my field placed less emphasis on a few selective journal outlets, and more on the quality and quantity of research ideas as a whole. The practice of evaluating a publication by the rejection rate of the journal in which it is published is ridiculous and unhealthy, and not conducive to academics’ main role of generating good knowledge.

- Research funding should be more evenly spread between labs and schools.

What did you want to be as a kid?

I wanted to be a writer. I guess I am one now, I just write about science!

Psyche Loui, above with her team from the MIND Lab – Music, Imaging, and Neural Dynamics Lab at Wesleyan University, is also on twitter (@psycheloui) and available online through her homepages

http://mindlab.research.wesleyan.edu/

11/13/2017: This week’s expert Elizabeth Parker, an academic mom and PhD candidate, talks about her fascinations for science and shares recommendations on how to keep a healthy work-life balance within this fast-pacing field.

Liyyz Parker (26y) and her son

Lizzy is a PhD candidate at the University of Sheffield (UK)

How did you get into research?

When I was choosing what to study at University, I knew I wanted to do Biology because I’d loved it at school, but I also wanted to continue with learning a language. Luckily I was able to do both, studying Biology at the University of Sheffield with an extra year in Dijon at the University of Burgundy. This meant my course was a year longer than most UK degrees and gave me lots of opportunity to try out working in a lab and get a better understanding of the research process … I enjoyed it so much that I decided to do a research Masters in plant and microbial biology. My Masters introduced me to the plant-soil-environment lab which I have worked in for five years now, as both a technician and PhD student.

What is your focus?

In my PhD research I work with a type of fungus called arbuscular mycorrhizae. These grow into the roots of about 80% of land plants and help the plant take up extra nutrients. In exchange, the plant provides carbon which is the fungus’ only energy source. We know that these fungi can benefit crop plants in many ways and I focus on how they help wheat to survive drought. We hope that this work will show us ways to maintain wheat yields as droughts become more severe and more common with climate change.

What is it that fascinates you about research and science?

I love finding out about how the world works and how people find solutions to big problems. Sometimes the way people have worked out how to find new information is just as interesting as the information they’ve found!

What are the biggest challenges?

Often experiments fail or we ask the wrong questions. However it all feeds into working out a better way to get to the bottom of things. We learn how to do things better next time … but sometimes, when you’ve worked on something for months, and you’re physically and mentally exhausted, then it can be so depressing that your experiment has “failed”! At these times it’s important to remember why you love your research field and why you got into it in the first place.

Looking back at your experiences, what’s your most important recommendation for a student deciding upon her/his field?

If you are applying for a masters or PhD then definitely make sure it is in a field you are passionate about. However, I would say that it’s not the only important factor. The scope of the project is also really important: will you have free rein or is there lots of built-in structure? Your supervisors will make a massive difference to your experience. I am very lucky to have had extremely supportive and understanding supervisors which has helped me grow in confidence with my academic work but has also been really important since I have been pregnant or breastfeeding for the whole of my PhD so far! PhDs last longer in some countries and it is definitely worth considering who you will be working with for that time as well as what you will be working on.

Do you feel you had to sacrifice a lot to get to the position you are in today?

I think sacrifice is a strong word! I would say at times I have compromised in order to be able to combine my academic work with other interests and commitments. For example, I lived in a different country away from my partner for a year to complete my undergraduate course which was tough but there were also lots of upsides (like amazing french pâtisseries!).

What are the challenges you are facing in your everyday life (i.e. in keeping a healthy work-life balance)? Can you give some advice on what worked best for you?

At the moment I have a 16 month old who is still breastfed and I am part way through my confirmation review for my PhD. I am also helping prepare some science communication activities and trying to keep my experimental plants alive. I am full-time funded but I am only in work 4 days a week. So I have a few challenges with work-life balance at the moment!

Having said that, I think my work-life balance might be better than before I had a child. I try to stick to strict lab/office hours and always be home by a set time. Having clear priorities makes me plan really carefully and I think I find it much easier to say “no” to extra commitments than I used to. I know there is not much opportunity for over-spill which makes me very focused. Because I have an extra day at home with my son I feel less like I’m “missing out” on his childhood than if I worked 5 days a week and it also gives my brain some time to relax. I think this is really important in a PhD and it would definitely be my main piece of advice for others: do something else sometimes!

Is there time for hobbies?

I love my work but it’s not my whole life. Now that I have a toddler I spend A LOT of time in the park (which is lovely in Sheffield because we have so many to choose from). I also knit and try to grow some food in our tiny garden (though this is more difficult than I would like to admit as a plant scientist!).

If you could change 3 things about the way the academic system works right now (publication, funding, hierarchy etc …), what would they be?

- Undergraduate funding in the UK is a big issue. The high fees and constantly changing goalposts for funding seem like they are shifting the emphasis of undergraduate degrees in a way which is causing problems for the whole academic system. Not only that but it may put off a lot of promising students because of issues with affordability or perceived value.

- There is a persistent idea that science is a slog and you have to work long hours. YES, you have to work, and sometimes the hours ARE long … but you can take a break and still do well.

- Linked to number 2, there seems to be a big taboo around mental health issues in academia. I think this is slowly starting to change but the competitive atmosphere of science can make it easy for people to burn out if good support structures aren’t in place.

Is there anything else you always wanted to tell a fellow scientist (older or younger) or any person interested in science?

Science is for everyone and if you are even remotely interested, you can participate. There are tonnes of citizen science projects out there where you can be involved in DOING science, not just hearing about it. https://www.zooniverse.org/projects is a great place to start where you can choose to help with projects as diverse as spotting galaxies, counting flowers for bees or sorting unidentified fossils.

What did you want to be as a kid?

When I was very young I wanted to be a lollipop lady. I just really liked their fluorescent coats. Then when I was a bit older I wanted to be a plumber or an artist.

What does your child want to be when they’re older and what is your response?

He’s a bit young to tell me, but based on his interests I’d say something with horses or trains! Or water or books or food or dogs … I want him to have a job that he loves!

You can also find Elizabeth on twitter: @parkerpannell

11/06/2017: This week’s expert Goren Gordon talks about his passion for the brain and his passion for quantum physics, about happiness, how to still keep a healthy work-life balance and shares advice to the upcoming generation of researchers.

Senior Lecturer, Head of the Curiosity Lab,

Tel Aviv University Israel (40y)

How did you get here?

My road was long and multi-disciplinary. I was 20 years a student in the university. I have a bachelor, masters and PhD in Quantum Physics, I have a bachelor in Medical Science and Masters in Business Administration and another PhD in Computational Neuroscience. I did my post-doc in MIT Media Lab in the Personal Robots Group. At almost any point in time I studied two degrees in parallel, because it was hard to reconcile my two great passions: quantum physics and the brain. In the end, I (almost) stopped my research in quantum physics and am now focusing on my admiration of the human capability to learn.

What is your focus?

My focus is Curiosity, from many different perspectives. I’m studying it using my physics background, by trying to formulate general equations of curiosity and building a mathematical model of curiosity. I’m implementing this model both in psychology and robotics. In psychology, I’m trying to use the model to better assess people’s curiosity, both adults and children. In robotics, I’m trying to create curious robots, that learn in similar ways to infants. The main goal is to understand infants by building infant-like robots.

What is it that fascinates you about research and science?

I’m thinking in equations because of my physics background. I’m always trying to simplify complex concepts into their bare minimum and trying to find this “one equation of the human mind”. While I know that is probably not possible, the fun is in the road to find it. It fascinates me to see infants and children learn by themselves so much and so fast. I wonder whether we will ever understand and be able to replicate that in robots. Furthermore, I learned about the possibility of social robots for education of children and it fascinates me that children can benefit so much from interacting with a social robot. I’m trying to combine these two seemingly-separate ideas, curious robots and curious children. What will happen if children continually interact with curious robots, that express enjoyment of learning, ask questions and explore? Will the child become more curious? Can we thus influence, promote and overcome the reduction in curiosity as children grow old? These are the questions that fascinate me and which I’m trying to answer through my research.

What are the biggest challenges?

There are challenges from different perspective. From a more fundamental point of view, the challenge is to understand basic human behavior and use reductionism to try and find a single principle underlying learning. There are so many aspects and the variability in human behavior is so great, it sometimes seems hopeless to find unifying principles.

From a robotics perspective, robots are hard. The only thing you can be sure of a robot is that it will break. They always break. Then you need to fix them in the absolute knowledge they will break again. However, this tests the researcher’s grit which is one of the most fundamental qualities of a successful scientists.

Then there are logistics. I am trying to run large studies in the formal educational system. There are so many bureacrats to deal with and so much logistics that it seems it is a full-time job just to coordinate the study, let alone run it, analyze it and publish it. But the gains from these large studies and the impact they may have are definitely worth the hassle.

Looking back at your experiences, what’s your most important recommendation for….

…a student deciding upon her/his field

Choose a field you are deeply passionate about. Disregard other people’s opinions, the job market or fads and trends. Find something that makes you smile whenever you think about it and makes you wake up in the morning with a sense of purpose and joy. All the other things will come from that.

…a post-doctoral researcher

Work hard but remember to enjoy the journey. There is always more work that can be done, more experiments to do and more papers to write, but you do not want to look back at this period in time as “I suffer now for the future”. The post-doc can be a wonderful time to explore, meet your future colleagues and do exciting things.

…a junior faculty

Hire a lab manager! From the start. The amount of bureaucracy is unbelievable and a lab manager, no matter how much he costs, is always worth it. Don’t wait for big grants to finance him, just hire immediately. As for students and labs, there are different ways for PI-ing, probably a different one for each PI-student combination, can’t help there. But some things are universal: in the beginning, you have no help from “senior-students”, because … you don’t have senior students, so it’s all on you. You have to train your students, so do it well and invest the time, it will repay in the future.

Do you feel that you had to sacrifice a lot to get to the position you are in today?

I made some unorthodox decisions along the way, but I always had in mind to enjoy what I’m doing now and don’t worry too much about the future. I learned early on that if I do what I love, I do it well and it pays off. I did have to sacrifice for my post-doc, which I did not want to do, but in hindsight it was a good experience and aided my career a lot.

What are the challenges you are facing in your everyday life (i.e. in keeping a healthy work-life balance)? Can you give some advice for the upcoming generation of researchers?

I read a lot about studies of happiness and there is a consensus on what makes people happy: surprise, surprise, it’s not work. It is their social circle and support. I actively invest energy and time to make the time to meet friends on a very regular and intense basis. I believe it is crucial and even though I have tons of work (don’t we all), I still make the time to play board games, meet friends, spend lots of time with the family. My best advice, which is probably the hardest to do, is to compartmentalize. When I’m at work I’m an orphan childless single researcher. When I’m at home, I’m an unemployed jobless father. If you can do that, everyone (including you) will be happy.

If you could change 3 things about the way the academic system works right now (publication, funding, hierarchy etc..) what would they be?

I would create many more truly multi-disciplinary positions. Today, most universities still hire based on faculty, even though so many researchers today are doing extremely multi-disciplinary work. It is extremely hard to land a job in engineering when you work with robots and kids, and vice versa. The same is true for publication and grants. While everyone loves to say they’re multi-disciplinary, in the end they judge by their own discipline and that’s so 20th century.

Is there anything else you always wanted to tell a fellow scientist (younger or older) or any person interested in science?

In order to do science you’ve got to have the passion. Without it, you won’t be happy and you won’t succeed. If you are passionate, don’t let anyone take it away from you; not editors of journals, not jealous colleagues nor grant committees. If you want to be a scientist, then you probably dream of changing the world. Go and do it and don’t let anyone tell you you can’t.

What did you want to be as a kid?

A scientist, from since I remember.

For more on Goren Gordon’s work visit his webpage: http://www.curiositylabtau.com/

10/29/2017: This week’s expert Hanna Dumont about educational research and remembering what science is actually about.

Postdoctoral research fellow,

German Institute for International Educational Research (34 years)

How did you end up in research?

I was still in high school, when the PISA 2000 study was published and revealed the high levels of educational inequality in Germany. I had a really great teacher who made the PISA study a topic in class. This is when I first learned about educational research. I don’t remember this, but my teacher told me many years later, when I had started my PhD in Educational Psychology that I told her back then, that I wanted to be an educational researcher.

What is your focus?

The early PISA findings that made me want to be in educational research also influenced my research focus: the study of educational inequalities! After having focused on factors in schools and families that cause inequalities I am now particularly interested in finding out, which pedagogical approaches can reduce inequalities.

What is it that fascinates you about research and science?

There is always so much more to learn!

What are the biggest challenges?

Because there is always so much more to learn, you sometimes don’t know when to stop!

Looking back at your experiences, what’s your most important recommendation for

…a student deciding upon her/his field:

do what you are passionate about!

….a doctoral candidate choosing a topic an research group:

choose a topic that your advisor is an expert on!

….a postdoctoral researcher:

fake it till you make it!

We are all great in handling success, but what’s your mantra to handle rejections?

I remind myself what really counts in life ! Plus eating good food!

What are key challenges we have to overcome?

My impression is that the pressure to publish has increased in recent years. I hope that we don’t forget that science is about advancing knowledge not finding as many least publishable units as possible.

10/24/2017: This week, Tobias Hauser, postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Centre for Computational Psychiatry in London, talks about his career path and experiences.

Postdoctoral research fellow,

Max Planck Centre for Computational Psychiatry in London (33 years)

How did you get to your current position in research?

During University, I worked with young people with mental health problems. Having seen how much impact such conditions can have and how little we still know about them, made me interested in understanding what happens in the developing brain for psychiatric disorders to arise. After graduating, I thus pursued a PhD in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry investigating ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) and OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder). During this time I realised how critical decision making in mental disorders are and that we have to understand the mechanisms that underlie these decision making biases. I then joined the Max Planck Centre for Computational Psychiatry in London, where I could investigate exactly this.

What is it that fascinates you about research and science?

Trying to understand the unknown is what drives me. Knowing that no one knows the answers to these questions, and that maybe I can help to shed light into how psychiatric disorders manifest.

What are the biggest challenges?

The academic system is a tricky one that comes with many challenges. Being a scientist means that you sometimes work for years with no obvious result and you never know whether your projects will work out in the end. Before you become a professor, you will be working a lot (often for little money) with a lot of uncertainty. You may not know where you will be working in a year’s time, or whether you will have a job at all. It is therefore not surprising that many (often of the smartest) are leaving academia along the way to pursue successful careers outside academia.

Looking back at your experiences, what’s your most important recommendation for….

…a student deciding upon her/his field

Do what you get excited about! Science is often a slow process with few rewards. This is why you have to love science whole-heartedly to succeed. If you want to do science, you will fail. Often. Things will not work. Things will take much longer than you thought. But don’t give up! Get up again and try again. Never give up. And finally, things will work out! And then, you expanded human knowledge! You discovered something that no one knew before. This is super exciting! And it is totally worth the many times of failing before and it will nurture you to pursue the next endeavour into the unknown.

….a doctoral candidate choosing a topic and research group

Do some serious research on what interests you and with whom you want to do research. Choosing a supervisor is a bit like choosing a (temporary) parent. You will work closely over the next several years with this person, you will work in topics that your supervisor is interested in, and you will probably be in close contact well beyond your PhD. It is not only the science that matters, but also the personality. If the latter does not match, the PhD can become rather difficult. Talk to lots of people and try to form an informed sense of how a potential supervisor will be and whether she is a good match for you.

What’s your approximate success/rejection rate for (papers/grants/job applications)?

Difficult to say. Some papers I only submit once, some I submit 10 times. And sometimes it is your best work that struggles the most with getting published.

We are all great in handling success, but what’s your mantra to handle rejections?

I wish I had one. It still hurts when your work is being rejected. Just be aware that you are not (only) your work. A rejection of your work does not mean a rejection of you as a person.

Where do you think the future of your field lies? What are key challenges we have to overcome?

I think it is critical to bring together different fields. Only this way we can overcome the challenges that we are facing. In my field this primarily means bringing basic and clinical neuroscience together. To understand psychiatric disorders, we must understand the computational mechanisms that underlie the decision making that is biased in mental health patients. We can only achieve that if we empower scientists to link these fields, to know the methods that this research requires and to conduct thought-through experiments that explain how decision-making biases arise, from neurons to cognition.

Personal Homepage/Links:

twitter: @tobiasuhauser

10/15/2017: Siobhan Pattwell is a postdoctoral research fellow and recipient of an early career research fellowship by the Jacobs Foundation for Youth Development. Check out her interview below to read more about Siobhan’s story on how she got into science, the motivational lines that keep her going and the challenges and exciting rewards science has brought.

Postdoctoral research fellow,

Holland Lab, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (34 years)

How did you get here?

I never had even the most remote dreams or plans to be a scientist. In fact, I never really enjoyed science labs in school – probably because they felt like busy work, took forever, and the teacher always knew the results beforehand. After switching my major several times in college (where I actually entered as a pre-law major), I finally settled on a combination of Spanish and Neuroscience with a pre-med track. I was fully geared up to spend a semester abroad in Spain. That specific semester unfortunately coincided with a peak in the ETA terrorist attacks in Spain, including the Madrid train bombings, and after some deliberation with my parents, it was decided that I would skip the trip.

With the spring semester well underway, I was incredibly fortunate to find a spot on London summer abroad program focusing on healthcare systems between the US and UK, organized by two amazing Lafayette College professors, Drs. Childs and Lammers. To say this trip was an eye-opener for me would be the understatement of my college career. As part of the program, we were given internships 4 days a week. Mine was at Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital with one of the most incredible physician-scientists I have ever met, Dr. Penelope “Peppy” Brock. Peppy is a consultant (senior physician) pediatric oncologist specializing in neuroblastoma at one of the most esteemed children’s hospitals in Europe. Needless to say, my world in the hallways at GOSH, as an aspiring medical student, was flipped upside-down. In awe of the dedicated staff of nurses, physicians, assistants, and therapists, I myself became increasingly frustrated at the lack of research and limited treatment options for some of the extremely rare cancer variants claiming the lives of the adorable British-accented children I played puzzle games with between exams. At one point, after asking Peppy (probably too many) questions about has “X” ever been tried, has “Y” ever been looked at, etc., she turned her head and with an enthusiastic smile said, “Oh, darling, you’re a scientist.” Peppy was right. I realized that summer that I needed to be the person who would try to understand some of these rare genetic events, to seek targets for better drugs, to search for novel treatment options. So, instead of taking the MCAT that summer like I had planned, I registered for the GRE a few weeks after the internship and the rest – is history.

What is your focus?

With a background in neuroscience, I have long been interested in the brain’s capacity for change – both in normal and abnormal plasticity. By exploring the role of growth factors – certain chemicals important for brain development – I hope to gain a better understanding of what makes certain pediatric conditions – ranging from brain tumors to psychiatric illnesses – difficult to treat and often subsequently treatment resistant. With a general fascination in neuroplasticity, I am particularly interested in how various factors can influence the development, survival, and behavior of various cell types within and outside the brain, both in normal development and in disease states ranging from psychiatric and neurological illness to cancer.

What is it that fascinates you about science?

The most exciting thing about science, in my opinion, is the possibility for discovering something new and seeing it for the very first time. Such novel discoveries may have been overlooked for decades and can often bring hope for further advancing science, medicine, policy, and ultimately lead to the development of new treatments for various illnesses or diseases.

What are the biggest challenges?

The biggest challenges go hand in hand with the most fascinating aspects. When seeking something new, you can’t just ‘google’ the right experiments to do or ask somebody if you found the right answer, since what you’re doing often has never been tried before. It’s a whole new way of thinking compared to the memorization of science classes or textbook learning in primary or secondary school. Often, there are many late nights and endless weekends in lab going through failed experiment after failed experiment, until maybe on the 100th try, something works!

Looking back at your experiences, what’s your most important recommendation for….

…a student deciding upon her/his field

My advice – this sounds like a joke, haha, it’s not – would be to invest in copies of Finding Nemo and Frozen. My friends and I often quoted Dory from Finding Nemo and would say “Just Keep Swimming” or even better, when experiments failed routinely, we were known to blast some Elsa in lab while singing along to “Let it go…” There will be a lot of times when you think things will never work and while some experiments may not, others may take 99 failures before the 100th time is a success.

Do you feel that you had to sacrifice a lot to get to the position you are in today?